Between 1983 and 1985, United States video game revenues dropped from $3.2 billion to about $100 million (Liedholm). The blame for the “video game crash” is largely attributed to Atari’s lack of regulation. Because anyone could create a game for the Atari 2600, everyone did. And when those companies went out of business, their unsold cartridges went to liquidators. As David Crane—designer of Pitfall—describes it, the liquidators bought brand new, $40 games “for $3, sold them to retailers for $4, and the retailers put them in barrels at the front of the store for $5. When dad went in to buy junior the latest Activision game for $40, he saw that he could be a hero and get eight games for the same money” (Donovan). Before the release of the NES in 1985, Americans believed that the home video game market was a fad that had run its course.

One of the reasons that Nintendo succeeded with the NES is that they required game publishers to “license” their cartridges, which required a certain level of quality assurance. While terrible games still came out (such as the infamous Deadly Towers) this process prevented the release of fundamentally broken games that couldn’t be completed.

But licensing wasn’t the only thing that happened around this time. Around the NES’s release in 1985, video game magazines started popping up to inform players about new games, printed strategy guides to help them complete difficult ones, and share players’ high scores. Video game journalism took a foothold after Atari’s passing, and ever since, reviews have become a point of contention for video game fans.

This month’s issue of The Backlog takes a look at a single game’s mixed critical reception and will try to figure out why video game reviewers disagree so much.

The History of Blobolonia

During the Atari’s lifespan, Activision published hundreds of games. Such hits as Pitfall (1982) are still remembered for pushing forward the adventure/platformer genre. In 1987, Bruce Davis took over as CEO and cut salaries for industried veterans, such as the designer of Pitfall, David Crane. Crane left with his colleague Garry Kitchen to form Absolute Entertainment.

Absolute created a handful of games, most infamously the never-released Penn & Teller’s Smoke and Mirrors. One of their best selling games was 1989’s A Boy and His Blob: Trouble on Blobolonia. A Boy and His Blob followed in the footsteps of Crane’s work at Activision by appealing to the most casual of video game players. “I stick to games that a normal person can pick up easily and enjoy 10 minutes away from that difficult spreadsheet” (Donovan). In the age of Ninja Gaiden (1988), Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out (1987), and Battletoads (1991), A Boy and His Blob filled in the gap for players who preferred exploration over twitch-like reflexes.

The Game, in Review

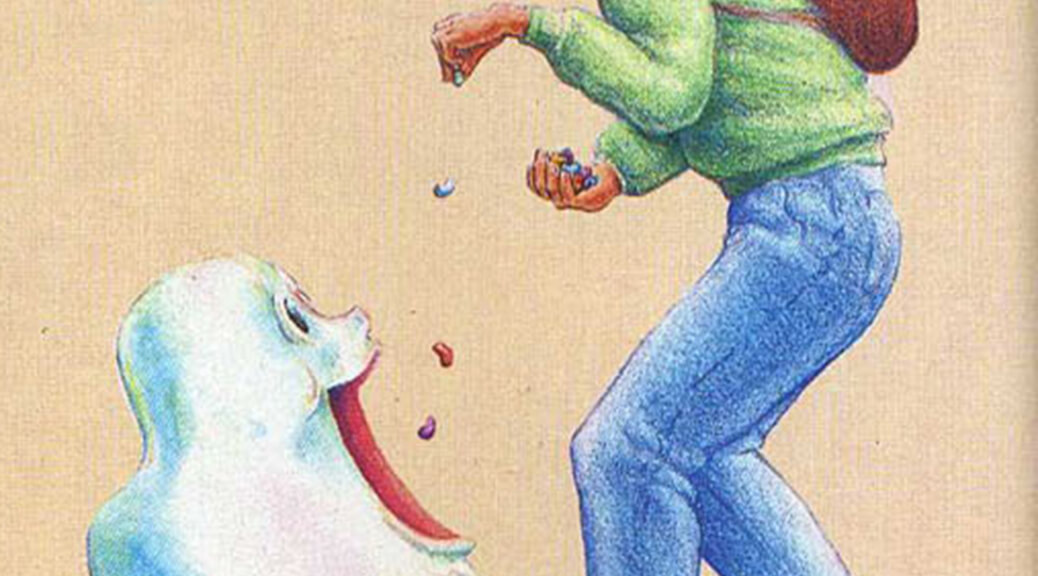

At first glance, the game looks like a side-scrolling platformer, except that the screen never scrolls and the player character (aka “the boy”) can’t jump. Instead of scrolling, each screen acts as a discrete room (much like Pitfall). And instead of being able to jump, the boy can only run and toss jelly beans. Following the boy is a white amorphous blob that bounces around in a playful manner. If the player makes the boy toss a jelly bean into the blob’s mouth, then the blob will morph into different items based on the flavor of the jelly bean. If he eats a cinnamon bean, he becomes a blowtorch. If the blob loses contact with the boy, then the boy can throw a ketchup-flavored jelly bean to make him “catch up”. The entire game is based around this mechanic of feeding the blob different pun-filled jelly beans in order to progress to the next screen.

A Brief History of Video Game Coverage

Play Meter launched in 1974, but targeted trade people, such as arcade vendors (Smejkál). The first consumer-oriented magazine came in 1981 with the British Computer and Video Games (Lee). A couple weeks later, the US launched the first magazine to focus exclusively on console games, Electronic Games (Plunkett). According to an encyclopedic article on USGamer, Jaz Rignall states that differences in the British and US magazine industries meant that UK magazines were better able to weather the storm of the video game crash between 1983 and 1985. In fact, the more popular US magazines—such as Nintendo Power and GamePro—didn’t see their first issues until the late ’80s. And those publications were solely promotional, meaning that they didn’t publish “reviews” of games, just previews and strategy guides.

Aside from British magazines, the ’80s had local newspapers and a couple US magazines. Video game content surged in the ’90s with publications like Expert Gamer, Game Informer, Electronic Gaming Monthly, Computer Gaming World, and so on, each with pictorial previews, interviews with developers, and detailed strategy guides. But as the rise of the internet led to aggregator sites such as Metacritic, “reviews” quickly became the most popular type of video game coverage.

Electronic vs Computer Games

In the early days, magazines that reviewed video games fit into two models: mags that only reviewed video games and mags that reviewed video games along with computer games and/or pen and paper tabletop games. VideoGames & Computer Entertainment published the first review for A Boy and His Blob saying it was the “perfect offering for those of you who are sick of the shoot-’em-till-they-drop/punch-’em-till-they-blink games that have been pounded out in droves lately” (Kelley). This review by Patrick J. Kelley ends saying, “It will delight players for many hours.”

Electronic Gaming Monthly was known for their “Review Crew”. While most publications tasked one writer with reviewing a game, EGM had all four of their reviewers offer their thoughts on each game. All four gave it a 5 or 6 out of 10, saying “There’s not a lot to the game play” and “the lack of scrolling screens and other rough edges do detract from the overall appeal” (Alessia, et al., 14).

Dragon—a Dungeons & Dragons magazine—says “This is definitely the game to buy if you are an NES gamer”, and they compliment it on encouraging experimentation. Mean Machines, a UK mag that focused on titles for the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64, gave it a 91%, saying that “Nintendo owners should go forth and purchase immediately!” (Leadbetter)

The pattern that emerges is that console video game reviewers criticized A Boy and His Blob for being unfriendly to the user while computer game reviewers praised the game’s need for experimentation. While there’s another essay to be written on the complex differences between mindsets of console gamers and computer gamers of the 1980s, the pattern that emerges from this low sample set implies that a player’s enjoyment of A Boy and His Blob depends on what games that person is used to playing. While this isn’t even close to definitive proof, it does point towards the idea that a review depends on the reviewer’s background and their familiarity with the medium. And that isn’t much of a surprise. Perspective is important. But is the reviewer’s perspective the only difference between reviews?

It’s Not About the Boy; It’s About the Blob

As part of the Review Crew, Ed Semrad of EGM left A Boy and His Blob with a positive impression—saying, “It’s a silly concept […] but it still plays well”—even though he gave it a mediocre 6 out of 10. Well, in The Milwaukee Journal, during the same month of March 1990, Semrad wrote a review in which he rated A Boy and His Blob an 8½ out of 10, even though his comments are not particularly complimentary. “The graphics are OK but not spectacular,” he says, as well as calling it “an updated version of ‘Pitfall’” (Semrad). Why would he give it a higher score for The Milwaukee Journal than for EGM, especially if his words weren’t as kind?

Basic essay writing classes teach Aristotle’s Rhetoric, a formal essay on creating persuasive arguments. Aside from the basic appeals to Logos, Ethos, and Pathos (i.e. logic, credibility, and sympathy), Aristotle focused his entire treatise on the idea that an argument should be tailored to a specific audience. With this in mind, it makes perfect sense that Ed Semrad would create different reviews for the same game. The casual audience of The Milwaukee Journal might better appreciate A Boy and His Blob even if it is “an updated version of ‘Pitfall’”. Similarly, the hardcore players who read EGM might dislike “a silly concept” that “looks like Crane’s 2600 titles”.

If a review is written as a persuasive argument, and if arguments are designed for a specific audience, then reviews must be designed for their audience. When asked about this for this issue of The Backlog, Editor-in-Chief of Vice Media’s gaming site—Austin Walker—said:

[E]very single outlet’s reviews differ from each other in big ways, and every writer worth their salt takes that into consideration. A Polygon review isn’t a [Giant Bomb] review isn’t a Gamespot review isn’t an IGN review. And it’s not that some of those sites do it “better” than others (though we all have our personal taste), it’s just that they have different audiences with different needs. And even when the writer might not take that into consideration, their editor definitely does!

Conclusion

A Boy and His Blob is a lovingly crafted puzzle/platformer created by one of the industry’s legends. While this issue of The Backlog is not interested in determining who should and shouldn’t play it, it has explored a multitude of places where opinions can be gathered and, more importantly, how those opinions can be weighed. After all, not everyone likes ketchup-flavored jelly beans. But if someone does, they need to know where to find them.

Coming Soon from The Backlog

Next month we’ll look an overlooked, yet influential, game. It will also be our first look at a total conversion modification for another game.

References, Sources, & Citations

- Alessi, Martin, et al. (Mar 1990). “Electronic Gaming Review Crew: A Boy and His Blob”. Electronic Gaming Monthly. Print.

- Donovan, Tristan. (08 Jul 2009). “The Replay Interviews: David Crane”. Gamasutra. Retrieved 27 Sep 2016 from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/6247/the_replay_interviews_david_crane.php

- Kelley, Patrick J. (Feb 1990). “A Boy and His Blob”. VideoGames & Computer Entertainment. Print.

- Leadbetter, Richard. (Jun 1991). “Review: A Boy and His Blob”. Mean Machines. Retrieved 08 Aug 2016 from http://www.meanmachinesmag.co.uk/pdf/boyandhisblobnes.pdf

- Lee, Dave. “Computer and Video Games online magazine facing closure”. BBC News. Retrieved 27 Sep 2016 from http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-27486867

- Lesser, Kirk, et al. (May 1990). “The Role of Computers”. Dragon. Retrieved 13 Aug 2016 from http://annarchive.com/files/Drmg157.pdf

- Liedholm, Marcus and Mattias. (01 Jan 2010) “The Famicom rules the world! – (1983–89)”. Nintendo Land. Retrieved 29 Sep 2016 from https://web.archive.org/web/20100101161115/http:/nintendoland.com/history/hist3.htm

- Nintendo Power. (Nov 1989). “A Boy and His Blob”. (used for cover images)

- Plunkett, Luke. (29 Dec 2009). “A Little Background On The World’s First Ever Video Game Magazine”. Kotaku. Retrieved 27 Sep 2016 from http://kotaku.com/5435951/a-little-background-on-the-worlds-first-ever-video-game-magazine

- Rignall, Jaz. (31 Dec 2015). “A Brief History of Games Journalism”. USGamer. Retrieved 27 Sep 2016 from http://www.usgamer.net/articles/a-brief-history-of-games-journalism

- Semrad, Edward J. (13 Mar 1990). “‘Thunder’ shows unlicensed games can be good”. The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 18 Aug 2016 from https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=7MYdAAAAIBAJ&sjid=CywEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6948,4356065&dq=boy-and-his-blob+nintendo&hl=en (no longer available)

- Smejkál, Péter. (08 Jun 2014). “18 dolog, amit nem tudtál a játékvilágról”. PC Guru. Retrieved 29 Sep 2016 from http://www.pcguru.hu/hirek/18-dolog-amit-nem-tudtal-a-jatekvilagrol/27743

What do you think?